Analysis: What Iraq reveals about Rex Tillerson

The would-be U.S. Secretary of State has a long foreign policy track record in Iraq, where Exxon aggressively pursued its interests, sometimes at the expense of political stability.

Rex Tillerson has never held a government position, but he does have a long track record of conducting foreign policy as the leader of ExxonMobil – one of the largest and most profitable oil companies ever.

He's likely to be confirmed as the next U.S. Secretary of State after hearings next week before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which will probe how his experience as a business leader might make him qualified to serve as the world's most powerful diplomat.

Exxon's activities in Iraq over the past decade provide a rich series of case studies that illuminate how Tillerson has negotiated with foreign leaders and pursued business interests aggressively – sometimes with little apparent regard for the political consequences.

Ever since the country's oil sector opened to foreign investment, in 2009, Iraq Oil Report has covered Exxon's saga in detail. Each chapter shows the character of the company, where Tillerson has spent his entire professional career, and provides insight into the worldview of the man who stands to shape U.S. policy toward Iraq, and the world, in the Trump administration.

1. Exxon lands its first deal in the new Iraq.

In the country's first oil contracting auction, in 2009, Exxon won the West Qurna 1 oil field. Although international oil companies (IOCs) generally regarded the government's terms as stingy, Exxon – like many other western companies – wanted to establish a foothold in the oil-rich nation, betting that the relationship could lead to further, more lucrative opportunities.

"ExxonMobil is used to doing large projects around the world. And this ranks up there with some of the largest," Rob Franklin, then-president of ExxonMobil Upstream Ventures, told Iraq Oil Report in an interview in February 2010. "All relationships, in my experience, have speed bumps in them. The important thing is to have a contract that both parties are happy with, to negotiate with good will and to work as hard as we can to fulfill the expectations both of the Iraqi government and of our shareholders too."

Just a year after Exxon got to work, West Qurna 1 hit a key production milestone that triggered additional payments for Exxon and its junior partner, Royal Dutch Shell. (Since then, it has taken the field to nearly 500,000 barrels per day (bpd) of production, or roughly 10 percent of the country's output.) The company was also tendering for engineering and design work for an important water injection project, Exxon's Iraq chief, James Adams, told Iraq Oil Report. The planned pipeline network was supposed to feed not only Exxon's project, but a half dozen of the other oil fields operated by IOCs – an essential project for Iraq to reach the ambitious production targets set in its various contracts.

Exxon appeared to be on track to becoming one of the Iraqi government's most important international partners. During this time, however, unbeknownst to government leaders in Washington or Baghdad, Tillerson and his team were getting ready to risk it all.

2. Tillerson expands to Kurdistan.

Shortly after getting to work on the West Qurna 1 project, Exxon started negotiations with the autonomous Kurdistan region, for six exploration blocks it would ultimately sign in October 2011. The decision came as a shock, and caused outrage in Baghdad.

Then-Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was furious that one of his government's key oil partners – an American firm that is commonly believed in the Middle East to be operating in sync with U.S. policy – was violating Baghdad's core belief in centralized oil policymaking. Iraq threatened to tear up the previous deals it had signed and, as Exxon was gearing up for exploration work in Kurdistan, the federal government said it would use military action to stop any drilling, raising the specter of a civil war.

For Tillerson, the deal revealed his ruthless focus on the bottom line. From his perspective, the contractual terms in Kurdistan were simply better than the opportunities that seemed likely to open up in Basra. Moreover, the company had hired a handful of former U.S. government officials with long experience in Iraq to provide political advice, and the upshot of their analysis was clear: Exxon had become so important to the Iraqi economy that the government could not punish Exxon without also harming itself. In Iraq, Exxon was too big to fail.

3. Turkey enters the picture, with Exxon as power broker.

Turkey had slowly been softening its anti-Kurdish stance with diplomatic outreach to the Iraqi Kurdistan region since 2008, but news of the Exxon deal jolted the government of then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan into a bold, geopolitical action. He perceived that the U.S., via its largest oil company, was effectively helping to create – and claim a large piece of – a new Kurdish oil sector right on Turkey's southern border. Turkey moved to claim a piece for itself.

By the end of 2012, Turkey and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) signed a game-changing energy protocol that promised to give the landlocked Kurds a way to export their oil by pipeline. It also outlined billions of dollars' worth of Turkish investment in the oil sector, and established the KRG as a major source for meeting Turkey's projected demand for natural gas.

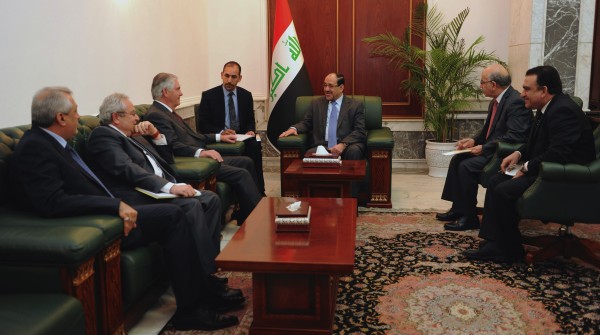

Tillerson himself played a central role in managing the combustible relationships with leaders in Baghdad, Erbil, Ankara, and Washington. He met with top federal Iraqi and Kurdistan region leaders several times, both to tamp down tensions and to solidify his interests.

Eventually, Exxon brought Turkey into all six of its Kurdistan oil projects. Before signing those deals, company executives insisted that Turkey prove it was committed to facilitate the KRG's independent oil exports. The opportunity to partner with Exxon was leverage – and Tillerson's team used it to ensure that the fruits of their Kurdistan investment would have a route to market.

Like many IOCs, Exxon endured the growing pains of a Baghdad government that was contracting multi-billion-dollar projects after decades of war, sanctions, and oil nationalization. Payment delays, logistical hassles, and newly stoked political tensions all took their toll. In 2012, Exxon began shopping around West Qurna 1, ultimately farming out shares to PetroChina and Indonesia's Pertamina.

In late 2015, Exxon again entered negotiations to work on vital southern Iraq infrastructure projects, which were supposed to be bundled into a deal that would also involve the development of two additional oil fields. After being removed from the crucial water injection pipeline project shortly after the Kurdistan deals were announced, Exxon was being courted again. But now, after a change in Oil Ministry leadership, that project apparently stands to be altered.

In Kurdistan, Tillerson's risks have yet to pay off. In mid 2016, the company gave up on developing three of the six blocks it originally signed due to disappointing exploration results. Even the three blocks it is keeping have not yet proven to contain the huge oil discoveries that Tillerson and his team had hoped for.